Counting Lizards: Unveiling Nature's Secrets with Community Science

“Preservation of our environment is not a liberal or conservative challenge; it's common sense.”

—President Ronald Reagan

“Good stewardship of the environment is not just a personal responsibility; it is a public value... Our duty is to use the land well, and sometimes not to use it at all. This is our responsibility as citizens, but more than that, it is our calling as stewards of the earth.” — President George W. Bush

“A cry for survival comes from the planet itself. A cry that can't be any more desperate or any clearer.” —President Joseph R. Biden

By DR. CAMERON BARROWS

Nature includes the total of creatures, plants, fungi, and bacteria that all work in concert to create and sustain the living world in which we exist and are a part. Nature is nothing if not resilient, having endured perturbations resulting from droughts, floods, wildfires, and ice ages. Every species we see today has survived those challenges. Still, the absence of mammoths, mastodons, ground sloths and saber-toothed cats from North America, where they were abundant just 20-40,000 years ago is testimony that nature’s resiliency has its limits. Today nature is being subjected to insults from invasive species, loss of predators, pollution, habitat fragmentation and destruction, and a new climate change. This time the climate isn’t getting colder, it is getting hotter, windier, droughts and flooding are more common, sea levels are rising, weather is more erratic. Is nature facing death from a thousand cuts, or will its resilience prevail? The answer to that question should dictate the urgency of our willingness to reduce the influence we humans have had on the current levels of those “insults to nature.”

Answering the question of whether species are at risk of extinction, early enough to reverse that trajectory, isn’t easy. Under the best of conditions nature isn’t static. Rather every year is different, different weather, different flowers, different pollinators, different lizard abundances. So how do we distinguish natural variations from trajectories toward a precipice from which nature may not recover? Measuring every species, tracking them over time to determine how their populations change in response to a changing environment is just not possible. Tracking rare species could make sense, but their rareness could make it hard to detect real change. A 50% decline from 20 to 10 individuals is a concern, but a decline from 200 to 100 individuals of a more common species is arguably more telling that something is amiss with their habitat. Tracking annual plants is problematic since they can “live” for decades, perhaps centuries, as viable seeds invisible to normal survey methods.

I have puzzled over this conundrum and have concluded that tracking groups of species that live in the same habitat, but occupying separate niches, may be the most efficient approach. Ideally, within this group of species there are vegetarians, insectivores, and predators, each potentially responding to environmental change in their own way. Importantly, these species need to be reasonably easy to count and common enough to provide sufficient data to detect real change. Species that are underground, strictly nocturnal, or evasive are not ideal candidates. Snakes are cool, apex predators, but their primarily nocturnal, stealthy habits would make it a challenge to be able to detect statistically significant changes in their populations. At least in a desert environment, better candidates would include insects, perennial plants, and lizards.

If species are negatively impacted by invasive species, we should expect their populations to decline in the presence of that non-native invader and remain more stable where that invasive species is absent. If species are negatively impacted by a warmer, drier environment, we should expect population abundance to be higher at cooler-wetter, higher elevations. These predictions allow us to distinguish random changes from changes precipitated by “insults to nature.” The only remaining task is to design a survey protocol that yields repeatable abundance data. That means that two surveys conducted at the same time of year and under similar weather conditions should yield the same species abundances.

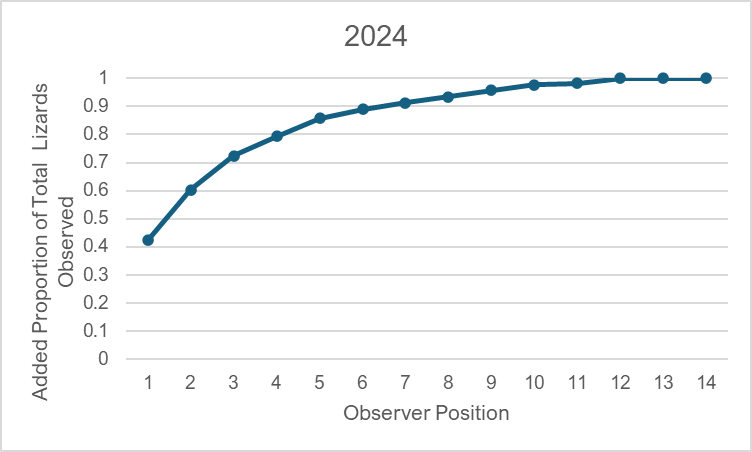

Initially I assumed, with admitted hubris, that I would see and so count every lizard along a desert trail. Easy, straightforward protocol for collecting lots of data. However, I had never tested that assumption. After all, how could I know how many lizards were present, and so how many I might miss seeing? My epiphany came to me on our group hikes, as I listened to our community scientists see and identify lizards that I had missed. Still, I couldn’t be missing more than just a few lizards… or could I be missing more than I realized? To test my assumptions, we have employed a protocol where I record the number of lizards I see by being first in line (so the same as if I was hiking alone), along with recording how many each of those behind me see, but I had missed. The results have been both humbling and exciting. I see 35-50% of the total lizards. That means that I am missing 50-65% of the lizards that were active along a trail on any given day. Our results show that the front 4-5 people in line consistently see 80% of the total lizards, and the front seven see 90%. Not until we have at least 10 community scientists all focused on counting lizards do we appear to have “seen them all”. Sometimes even a person at the end of the line sees a lizard that up to nine people in front of them missed. This is the first time I am aware that the added value of community scientists has been quantified. With more precise data we can have greater assurance that we are accurately assessing the impacts of environmental change.

Nullius in verba – Go outside, tip your hat to a chuckwalla (and a cactus), and think like a mountain