Little things make a big difference

“Little things make a big difference.” — Yogi Berra

Lumping all the North American Deserts together as a single ecological landscape would make no more sense than combining redwoods and pinyons to define the conifer forests. They are different. Organisms that live in deserts are different and the conditions that either support or constrain life there are different. The question then is how many North American Deserts are there? Most historical maps show four deserts, the Great Basin, Mojave, Sonoran, and Chihuahua Deserts. That quartet is ingrained in many naturalists’ minds, but it is it right?

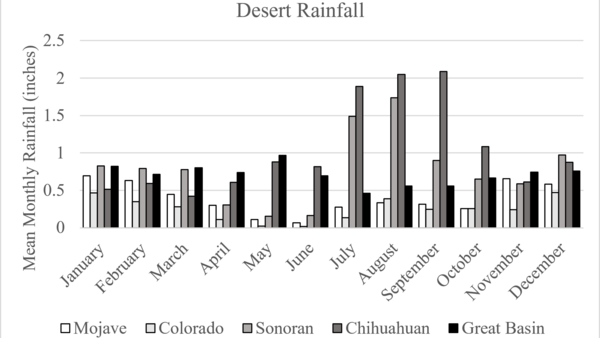

Precipitation defines deserts. Typically, any landscape that averages 10 inches or less is considered a desert, although it is more meaningful to describe whether that rain or snow is available to the plants or animals that live within that landscape. In terms of absolute precipitation, the two wettest deserts, the Sonoran and Chihuahuan, receive most of their rain as summer monsoons when temperatures are bouncing at or above the century mark; a significant amount of that rain evaporates before it can be absorbed into plant roots or lapped up by animals. The Great Basin Desert is the next wettest, but much of that rain falls as snow when the ground is frozen and animals are hibernating. Using this understanding, rainfall patterns still can define individual desert types. However, when we use rainfall, a fifth desert becomes apparent. That fifth desert is by far the driest and hottest and has been named the Colorado Desert because of its juxtaposition with the lower Colorado River. Still, even newly published desert field guides often fail to recognize this fifth desert, rather considering it a hotter and drier subset of the Sonoran Desert. The Colorado Desert’s rainfall patterns are actually much closer to that of the Mojave Desert, but higher elevations and again cooler temperatures of the Mojave mean that more of the rain falling there can be utilized by plants and animals, whereas the hotter Colorado Desert evaporates much more of the rain that falls there, making it by far the most arid of North America’s deserts. The Colorado Desert includes the Coachella Valley, north to Twentynine Palms and Needles, and extends south into northeastern Baja California, where it then is replaced by as many as five desert types extending south down that peninsula.

The five North American deserts described here (north of Baja California) have some overlap in what lives there, but there are species unique to each. Creosote bush dominates the Chihuahua, Sonoran, Mojave, and Colorado Deserts, and ocotillo occur throughout the Chihuahua, Sonoran and Colorado Deserts. Junipers, pinyons, and antelope bitterbrush (Purshia tridentata) are shared among the Mojave and Great Basin Deserts. These plants have evolved broad niches that span the moisture and temperature boundaries of each of our deserts. Then there are those species that almost define a single desert type. These species have somewhat narrower niches: sagebrush in the Great Basin Desert, Joshua trees in the Mojave Desert, California fan palms in the Colorado Desert, Saguaro cacti in the Sonoran Desert, and Lechuguilla agaves in the Chihuahua Desert. Each of these species highlights the between-desert diversity characterizing our deserts.

It cannot be overstated — water is the critical ingredient for life on our planet. Where water is limiting, as in deserts, the ability for plants and animals to exploit that precious resource becomes a primary driver for natural selection and the creation of new species. Certain soils (like sand dunes) are better at holding on to what precious rain falls from the skies. Where there are moisture gradients associated with proximity to rain-shadowing mountain ranges, elevation, slope aspect, fault zones, springs, ephemeral washes, and soil types, animals and plants track those gradients. Each of these moisture gradients represent series of more narrow niches to be exploited by plants and animals with the result of much higher levels of within-desert species diversity than one might predict if viewing the deserts macroscopically. Common sense tells us that hot, dry places should be limiting to life, not a catalyst for species richness. Yet in deserts localized differences in moisture availability have been the catalyst for species richness, explaining the high biodiversity on what otherwise appears as a parched landscape. During cooler-wetter climate cycles, such as the multiple glacial maxima during the Pleistocene, species were not as confined by extreme aridity and so could broadly distribute themselves across landscapes. When aridity inevitably returned (glacial minima) only those individuals that were situated along moisture gradients according to their physiological requirements could persist. There, isolated from other populations, natural selection could act on random mutations, some of which have allowed species to become increasingly better adapted to thriving under otherwise hyper arid conditions. Today, within the Colorado Desert and its associated sky island mountains, the hottest and driest desert of North America, over 5000 native plant species have been found. Our deserts are not barren wastelands.

Large differences in how and when rain falls in deserts defines desert types across the North American landscape. Small differences, along isolated moisture gradients, define where species occur within those deserts, fostering biodiversity. Those small often subtle differences will almost certainly change in character as modern climate change is creating unprecedented levels of aridity. How or if the monsoons will change, and how the multitude of moisture gradients will be affected will dictate which species will find a way to survive and which might not. Little changes might make a big difference.

Nullius in verba

Go outside, tip your hat to a chuckwalla (and a cactus), think like a mountain, and be safe