Desert Oases

“… in a desert you only regret the oasis you let pass.”

Deserts challenge life to exist. Yet animals and plants residing in deserts offer an extraordinary number of examples of how natural selection has overcome these extremes of heat and aridity to let life happen — and in many cases thrive. But then there are palm trees, a family of plants that originated in the wet, warm tropics.

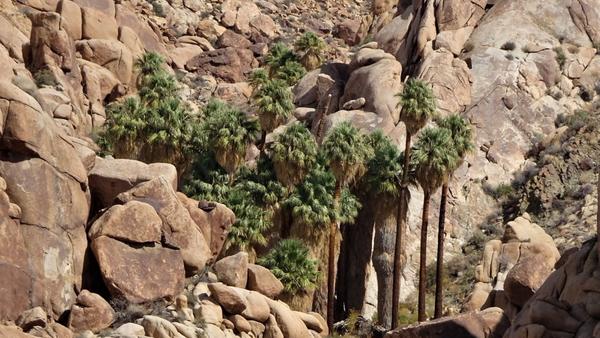

Rather than having adapted to desert conditions with small, waxy, gray, and/or ephemeral leaves that sparingly give up their precious water while converting sunlight into the building blocks of life, palm trees hold on to their tropical adaptations, sporting huge bright green ostentatious leaves that spew water molecules through their stomata. Why? Because they can; they can only live so extravagantly where their roots have access to a limitless supply of near-surface water. They waste water because where they live there have been no limits on that precious resource.

Our desert fan palms, Washingtonia filifera, typically exist where earthquake faults have forced deep ground water to the earth’s surface. They are only found in the Colorado Desert, that drier, hotter neighbor of the Mojave and Sonoran Deserts, and their native range is almost completely restricted to California and northeastern Baja California. There is one natural palm oasis tucked up into a narrow cleft in the rocks, just over the Arizona border in the Kofa Mountains National Wildlife Refuge.

In Baja they are joined by three additional species of palms, all similarly restricted to rare creases in an otherwise parched landscape where water comes to the surface. But has it always been so? What about during the ebb and flow of cooler wetter conditions during the Pleistocene’s glacial maxima and the warmer drier conditions of the glacial minima? There were never ice sheets covering the Colorado Desert, but during those glacial maxima it was a very different place, possibly covered with oaks, pinyon pines, junipers, and Joshua trees, with giant ground sloths, camels, horses, and mastodons. Naturalists have speculated that the saw-tooth edges of desert fan palm petioles (leaf stems) were an adaptation to thwart herbivory by giant sloths and mastodons. As the palm trees grow above what would have been the reach of those giant beasts, the saw-tooth edges on new leaves disappear.

Were desert fan palms part of that Pleistocene landscape? They do not coexist with pinyons, junipers, and Joshua trees today in the Mojave Desert. However, the palms do occur today in the Santa Rosa Mountains including elevations near and above 3000’, with junipers and pinyons nearby. During the Pleistocene were the palms shunted south by colder temperatures or did they become more widespread due to higher rainfall and so elevated groundwater levels? There is also an additional factor to consider; these palms were utilized by those first people to live here, for both food (sweet, date-flavored fruits) and for building materials. Did those first people influence the palms’ distribution? Did the cold temperatures push the palms down into warmer Baja California, only to be brought back by these enterprising people? Or were they here all along, and perhaps were more widespread? Is the distribution of desert fan palms today a shadow of a broader distribution, or is it an artifact of people planting them, acting as “Johnny Appleseed” with palm seeds brought from Baja California?

A definitive answer to these questions will always be elusive, but there are some clues. If people were planting the palms, we might expect that the palms’ distribution would be centered on human habitation sites. Many are: Palm Canyons, Thousand Palms Canyon, Willow Hole, Corn Spring, and more were all sites where Cahuilla villages or family groups lived at least seasonally. Most other palm groves are nestled in steep canyons and probably would have only been occasionally visited by people. Perhaps those sites were “planted” by coyotes, robins, or bluebirds, all known to eat palm fruits and then move between water holes.

There is another clue that might be more helpful – a beetle. The giant palm-boring beetle, Dinapate wrightii, is indeed a giant among beetles, and it is specifically found in association with palms, especially desert fan palms. To be very clear, this is a native species, not the introduced Asian palm weevil, Rhynchophorus ferrugineus, currently killing palms in coastal areas of southern California.

Adult giant palm-boring beetles are clumsy fliers, prized by beetle collectors in the 19th and early 20th centuries. One story goes that the very first specimens of this beetle were found in palm oases in the Coachella Valley, but that original collector kept the location secret for years while he made quite a bit of money selling the specimens to collectors in Europe and Asia. The adult beetles live for just a few days of frenzy trying to find a mate and then lay eggs in the crown of a palm tree. The eggs hatch into beetle larvae that then attempt to bore into the palm, and if successful, will live there for about seven years munching their way creating channels of sawdust throughout the palm’s trunk. Healthy palms with an ample water supply can resist the entry of the beetle larva or tolerate the few that do get in, but if water-stressed and infested with lots of larvae, the beetles can speed the palms on their trajectory toward death a bit sooner. The beetle larvae then pupate, emerging as adults through the wall of the palm trunk, leaving a species-specific quarter-sized hole, and starting the frenzy again. This dance between palms and beetles has been going on for at tens of thousands of years, probably far longer. No winners or losers, just nature happening. Still, our “modern” sensibilities have left the beetle as a villain, something to be controlled and killed, even though the beetle and palm have coexisted for millennia.

The reason the beetle could be helpful in answering our questions about the current palm distribution is that they seem to be clumsy fliers — meaning they might not be able to travel very long distances to occupy a new palm grove, and the first people occupying this land would have had no reason to help them arrive here nor spread from oasis to oasis. Every palm oasis I have visited that did not have a modern origin (not planted by people within the past 1-2 centuries), including Corn Spring in the Chuckwalla Mountains, which is separated from the next closest palm oasis by more than 25 miles, has trees with tell-tale giant palm-boring beetle exit holes on at least some of the palm trunks. There is a palm oasis at Cottonwood Spring in Joshua Tree National Park with a modern, circa early 20th century, origin, and is just 3.5 miles from a natural oasis (Lost Palms Oasis) with many palm boring beetle exit holes, but the Cottonwood Spring Oasis has no evidence of palm-boring beetles. So, given the widespread co-occurrence of the beetles and native palms, and the beetles’ absence from “new” oases, one reasonable conclusion is that the palms (and the beetles) have been here a long time, through the ebb and flow of colder-wetter and then warmer-drier conditions that characterized the Pleistocene era and before, and at some point, perhaps before the Pleistocene, they were distributed more continuously than the isolated oases we see today.

Today, many palm oases are threatened by climate change, not palm-boring beetles. For many the ground water that allowed the palms to become established no longer reaches the surface, and so there are no young palms recruiting into the oasis to replace the old giants. Less snowpack, hotter conditions, increased drought severity are all resulting in less water entering the mountain aquifers. In some cases, those aquifers may have been filled by the wetter conditions of the Pleistocene and are now finally drying up. The Corn Springs oasis is perhaps such an example, as in a very short time, just a decade or two, it has gone from being a vibrant oasis to today having mostly dead palm trunks and a few water-stressed trees.

Those palm oases that still have ample water coming to the surface, like the Palm Canyons south of Palm Springs, Thousand Palms Canyon in the Indio Hills, and 49 Palms Oasis in Joshua Tree National Park, are all examples of the previous grandeur of what palm oases throughout this region once were. In many ways these oases are acting as climate refugia, providing cooler-wetter conditions where plants and animals that once roamed across this region during the Pleistocene’s glacial maxima. Lizards and plant species that are otherwise relegated to much higher elevations can be found thriving in low elevation palm oases. You won’t find a giant ground sloth, but you can find western fence lizards, western skinks, orchids, fuchsias, poison oak, and others.

Nullius in verba

Go outside, tip your hat to a chuckwalla (and a cactus), think like a mountain, and be safe.