What were the effects of the Mountain Fire?

“Humans are pattern-seeking story-telling animals, and we are quite adept at telling stories about patterns, whether they exist or not.” — Michael Shermer

“From where we stand the rain seems random. If we could stand somewhere else, we would see the order in it.” — Tony Hillerman, Coyote Waits

Scientist too are storytellers, pattern seekers. We call them hypotheses. The difference from the other storytellers is that scientists do our best to test our hypotheses to determine if those patterns do exist, whether they are in fact real. If they are not, we modify them or outright reject them and move on.

In a little over a month, it will be eight years since the Mountain Fire — ignited by a faulty electrical box near Mountain Center — swept westward buoyed by strong winds over the crest of the San Jacinto Mountains, nearly reaching the city limits of Palm Springs. It was 2013, the second year of what would turn out to be five years of below average rainfall, well below average. Unlike the first people to inhabit these lands, people who used fire as a tool to improve the resources on which they depended, our European-based belief systems place wildfires firmly in the category of disasters. Add a five-year drought on top of a wildfire, and we had a double ecological disaster. Or so I predicted.

Serendipitously, a week before the Mountain Fire ignited, I was hiking in what would be the path of that fire. I was looking for a series of trails that climbed into the mountains to embark on a long-term study of how, or if, a warmer, more arid climate would impact the lizards living along those gradients. Ranging from 4,800’ to over 6,000’, the Spitler Peak trail looked like it might fit my needs. Hiking that trail, I found just a few side-blotched lizards, but only at the lowest elevations. I knew this species was far more abundant at still lower elevations, so this looked like the upper limits of their range – perfect to detect change as the climate warms. I also found southern sagebrush lizards, a high elevation species that can occur at elevations well above 8-9,000’ in our local mountains. But on the Spitler, they were there at 5,600’, the lowest elevation record for anywhere in these sky island mountains. Again, perfect to detect the impacts of climate change.

Then, just one week later, the fire ignited and stormed across the Spitler Peak trail on its way to the mountain crest and beyond. The above ground, living portion of every shrub and tree was incinerated. All that was left were the standing snags of oaks and conifers that just a week before had formed a shady canopy for much of the hike. Whatever lizards survived the fire would find a charred landscape with nothing to eat and nowhere to escape the heat of the day. It would be like looking into a crystal ball to see a world perhaps a half of a century from now, a world that had been ravaged by climate change.

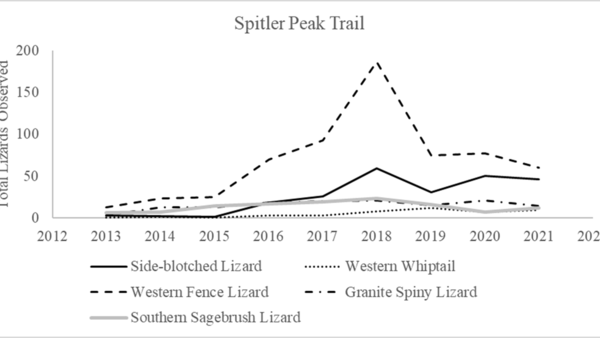

Exactly one year after my first survey, I went back to Spitler expecting to find almost nothing left. In 2013 there had been a rich mixed evergreen forest that included five species of conifers and dense stands of black and canyon live oaks. In 2014, except for a mere handful of Coulter pines that escaped the fire by selecting habitats in unburnable outcrops of granite, all the other conifers were gone. The oaks were a different story. Yes, their above ground trunks were scorched snags, but almost every plant was sprouting vigorously from the root crowns. And the lizard population was essentially unchanged from the year before. In 2015 and 2016 it was much the same. No new conifers, the oaks’ crown sprouts were getting bigger, and surprisingly the lizard numbers were growing. The side-blotched lizards were beginning to occur at increasingly higher elevations, but the southern sagebrush lizards were still where they were in 2013.

The next year, 2017, rainfall levels were well above average; the drought was at least temporarily broken. There were carpets of fire-following annual plants, and with them there were abundant and diverse insect pollinators. Lizard food was abundant, and a bumper crop of young lizards joined the populations, as evidenced by the sharp rise in numbers measured in 2018. The side-blotched lizards went from being the rarest lizard species, to becoming the second-most abundant, and each year we found them at higher elevations. The southern sagebrush lizards (along with the granite spiny lizards and western whiptails) just keep chugging along with little or no change.

Our cadre of community scientists and I just completed the 2021 survey. Thanks to their sharp eyes, for the first time since the fire, we found some seedling conifers. Birds are abundant in this young forest: lazuli buntings, Bell’s and black-chinned sparrows, spotted towhees, violet-green swallows, western bluebirds, and many more. The swallows and bluebirds are hole nesters and are clearly taking advantage of the plethora of snags.

The side-blotched and western fence lizard populations seem to have found a new population “normal” that is many times higher than levels before and immediately after the fire. Why have they responded while the other lizards have not? One reason is that they are sun worshipers — active thermoregulators that move in and out of the sun, to keep their body temperature more or less constant and high throughout the day. The fire’s removal of the original dense overstory canopy has allowed much more sun to hit the rocks and ground, giving them many more options to maintain their body temperature at optimum levels. In contrast, southern sagebrush lizards are shade-loving thermal conformers, allowing their body temperatures to fluctuate with air temperatures. Curiously, granite spiny lizards are also active thermoregulators, but their numbers have not changed. Perhaps there are other factors limiting their population size?

The story of the effect of the Mountain Fire is still unfolding. However, it has not proved to be an ecological catastrophe. Rather the story appears to be one of diversity, regeneration, and revitalization. Many of my preconceptions proved wrong, although the side-blotched lizards expanding their populations incrementally into higher and higher elevations does fit my original hypothesis. It is obviously much more complex than I had originally thought. It always is.

Nullius in verba

Go outside, tip your hat to a chuckwalla (and a cactus), and be safe.