What community means in ecology

“The more clearly we can focus our attention on the wonders and realities of the universe about us, the less taste we shall have for destruction.” — Rachel Carson

Ecologists (naturalists) seek to understand patterns in nature at different scales. One of those scales focuses on individuals within a species (autecology). At this level one might look at individuals to see what they eat, how much water they need, or how they otherwise interact with their environment, and how those interactions might affect their longevity and recruitment. Or one might take it to another level and look at how individuals within that species interact with each other and ask questions such as how many individuals are required to sustain a population of that species, how or if individuals move between populations, or what level of genetic diversity is required to have a sustainable group (population ecology).

At a much larger scale, studies focus on how energy flows through the environment. How solar radiation and minerals and nutrients and pollution, and natural processes such as flooding and fires and wind storms interact to foster a particular assortment of living things (ecosystem ecology). Then there is a middle ground where you could ask whether there are combinations of native plants and animals that are regularly found together in particular settings and is so how those combinations change over space and time (community ecology). At every scale the questions are different and so to are the levels of understanding to be gained.

The term “community” has a different meaning for a naturalist than it has for a city planner. For the city planner a community might be a group of people who choose to live in a neighborhood, or perhaps too often it might not be so much a choice, but due to other restrictions imposed on people to live in a neighborhood because of economics or ethnic similarities. In its most positive meaning, a community represents people working together for the common good. However, for the ecologist/naturalist, a community refers to a collection of interacting species, and questions focus on how stable that collection is between sites and over time, how those species interact with each other, and what happens when a new species (like and invasive weed) enters the mix.

Community ecologists look at the composition and size of trophic levels, plants, herbivores, and predators. Plants form the broad base of those trophic relationships, although in some cases the plants and those that consume the plants can live in very different places. Such is the situation on active desert sand dunes and small desert islands. Both habitats can support a rich and abundant community of organisms, but for both, plants have a difficult time becoming established. For the dunes, its hyper aridity and a very mobile surface layer inhibiting plant growth. For desert islands its also hyper aridity, often a lack of soil, and an inhospitable ocean barrier. So how do these habitats overcome their lack of plant growth to support their rich and diverse communities? Ecologists have come up with a big, difficult-to-pronounce word, allochthonous, to describe what are typically plants or other foods that are moved from their origin to a new habitat. Often it is the wind that delivers seeds and plant parts from more stable soils elsewhere on to the dunes. Or it could be ocean currents delivering kelp or other vegetation on to a beach, or it could be sea birds delivering food to nesting colonies on those desert islands.

In the Gulf of California, one of the islands, Isla San Pedro Martir, is an important nesting site for brown and blue footed boobies, and brown pelicans. Very few plants grow there, the dominant being tall columnar cardon cactus. Still, there is a rich community of insects and two endemic lizard species, a side-blotched lizard and a whiptail. The insects and lizards’ primary food source are the bits of uneaten fish that accumulate around the nestling sea birds. One way or another all communities are dependent on plants to form the base of a food web (the fish food web starts with phyto plankton).

If climate change ultimately results in species extinctions, at least in deserts it will not be because of it just getting too hot. It will be because heat, coupled with less rain could make it too arid for plants to grow. Without plants, communities will collapse. When we have a particularly dry year, like 2021, you can see how such a collapse could take place. Little or no annual plants germinated at the lower, more arid, elevations. That means no food for pollinators, vegetarians, or ultimately detritivores. Most of these are insects, but there are two big vegetarian lizards and a tortoise here in the desert, chuckwallas and desert iguanas and the Mojave Desert tortoise. For those species, this is not their first drought, and being reptiles, they can go one or more years without food or water and can still survive. Last year was wetter than average and so these reptiles were able to breed and still put on lots of fat; the adults will make it through a year or two or more of famine. Unfortunately, their hatchlings, products of last years’ cornucopia, will not have those fat stores to get them through the year.

Side-blotched lizards, small, short-lived insectivores, will also have a tough time at lower elevations during droughts. With the sequence of droughts over the past couple decades we have seen these lizards incrementally shift where their populations are most abundant to higher and higher elevations where it is less arid and there are more annual plants surviving and more insects, and so more lizards. In nature’s communities there are many connections, and side-botched lizards are a primary food for many species of predators, including western whiptails, collared lizards, leopard lizards, roadrunners, kestrels, and California scrub jays. I can imagine, because of the plenty catalyzed by several years of above average rain, there could be lots of chuckwalla and iguana hatchlings and side-blotched lizards, which could fuel a population surge in that predator guild. Unfortunately, a surge followed by a crash. Lots of predators plus drought could deplete the small lizard populations leaving little or nothing to support the larger predators, resulting in a negative spiral.

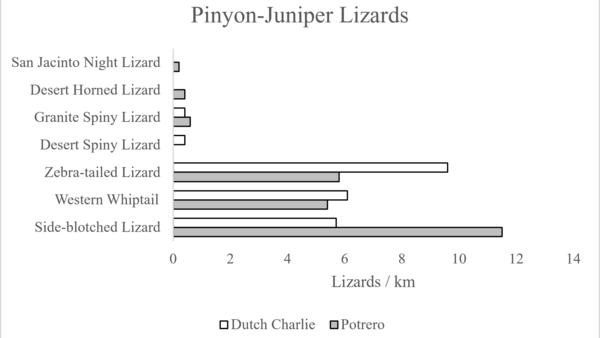

“Nature is not more complicated than you think, it is more complicated than you CAN think.” — Frank Edwin Egler. But community ecology gives us a way to chip away at the edges. We (community scientists and I) have been surveying lizards at the lower edge of the pinyon-juniper forest community the last couple weeks. What you can see from this graph is that there is a close level of similarity between the two locations. Imperfect, but close. The differences can fuel the development of hypotheses trying to explain those differences. The biggest difference was that there was nearly twice the density of side-blotched lizards in Potrero Canyon than Dutch Charlie Canyon. Also, more zebra-tailed lizards in Dutch Charlie. But why?

Two ideas come to mind. Potrero is wetter and seems to have a higher level of plant diversity. That might provide a buffering effect from the drought for the side-blotched lizards. Zebra-tailed lizards are nearing their elevation limits at these sites; otherwise, they occur on hyper-arid desert flats. A drier Dutch Charlie should not be a problem for the zebra-tails. Both observations are consistent with a wetter Potrero – more arid Dutch Charlie causal effect. Also, I noticed more California scrub jays, potentially a side-blotched lizard predator, in Dutch Charlie. Zebra-tails my be too fast for the jays to catch them.

I’m attaching a picture of one of those large predators of side-blotched lizards. Who will be the first to identify it?

Nullius in verba

Go outside, tip your hat to a chuckwalla (and a cactus), and be safe.