The value of having 'new eyes'

“The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.” — Marcel Proust

Discovery, and then independent confirmation, is both the essence and the joy of doing science. That second, confirmation step is what sets science apart from other ways of learning. Children are natural scientists, carefully observing their world and then testing their discoveries with smell, taste and touch and repeating those sniffs, tastes and touches that give them joy. Older scientists are those who have not forgotten nor lost that early overwhelming curiosity about the world on which we live. It is a rare walk in nature when I could not say that I discovered something new. Sometimes those small discoveries, adding up over time and placed in broader contexts, then gain significance; no new discovery, however small, should be discounted. “Eureka!” moments for discoveries that change how we think nature works are rare and elusive, but there is also joy in the smaller discoveries that alone may just give one pause with the realization that “I learned something new today."

Proust’s “new eyes” has a dual meaning. Isaac Newton once opined that "no great discovery was ever made without a bold guess,” (a.k.a. a hypothesis). Hypotheses create a new framework for how to interpret observations; subsequent observations or discoveries either support or refute a hypothesis. That new framework creates “new eyes” from which discoveries can be made. However, there is another meaning that Proust may have not considered; discoveries (science) need not be a solitary venture. Increasingly scientists are enlisting multidisciplinary teams to tackle challenging questions. Those team members constitute new eyes which then view the question and subsequent observations from different backgrounds and knowledge bases.

My multidisciplinary team includes graduates of our California Naturalist course, along with a few who will hopefully someday become graduates. What they have in common is a curiosity about our world. Otherwise they come from different backgrounds, some have college degrees, others do not. Of those with degrees, some were in science, some wanted to go into science, but circumstances lead them in other directions, and others are just interested in learning. Together they are indispensable “new eyes."

The past couple weeks our team has been surveying vegetation and lizards on the Boo Hoff trail. This trail is nearly in my backyard, and one that I hike solo at least a half a dozen time each year. So, Friday we set off with me, as always, taking the lead and setting the pace. It was not long until one team member spied a small herd of bighorn sheep up on the ridge. I would have never seen them. Then another team member found a small, delicate pea plant in bloom, Marina parryi, Parry’s dalea, a perennial that is at the very northwestern edge of its range there on the Boo Hoff trail. It has been there for each of the many dozens of times I have hiked that trail, but this was the first time we have met.

Another team member has become fascinated with “bugs." Knowing this, when we were counting plants in one of our permanent plots, I saw one of those bugs scurrying in front of me and so gently picked it up to show her. Her enthusiasm is infectious, and before releasing it we spent several minutes photographing the bug from every angle so that someone on the iNaturalist web site will be able to identify it. Each one of these team members is making contributions. Each one is a set of “new eyes."

It should come as no surprise to anyone that I really like lizards, and often incorporate lizards into the research I do. Whereas previously I typically surveyed those lizards while hiking local trails solo, increasingly that research is incorporating our team of community scientists. One of my questions has been, that if we only count lizards along the narrow desert mountain trails, what is the contribution of those added team members stretched out in single file along the trail and how many added observers will it take before adding any more doesn’t improve our lizard counts? This fall we have been collecting the data to answer these questions. I always take the lead, and so my observations constitute what the count total would be if I were doing the survey alone. The following team members were encouraged to change positions often so as not to bias any one position in our line if a person is a better lizard spotter than another. They just yelled out their position and what species they saw. If the lizard had not previously been seen by me or another team member, the observation and the position of the observer were recorded.

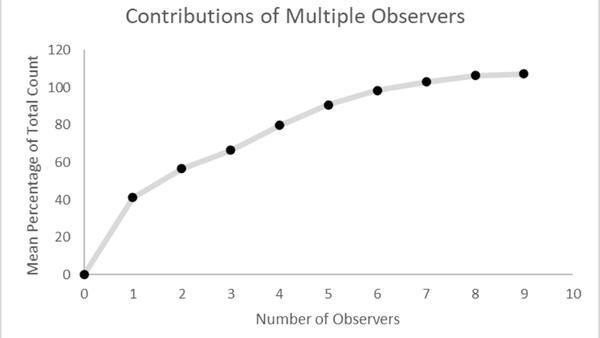

I have added a quick graph to illustrate our result compiled over seven trails so far this Fall. Again, I was always in position #1, and being in the lead I would expect to the most lizards, which was the case. However, on average, I saw just a bit over 40% of the total lizards recorded. Each of the next 5-6 observers added, on average, another 10% to the total. Only when there were more than seven total observers does the graph reach an asymptote (level off) where added “new eyes” unable to add significantly to our totals. It is a bit humbling to know that on my solo lizard counts I was missing as many as 60% of the active lizards that day. Adding “new eyes” increases our discoveries and adds to the joy of doing science.

Unfortunately, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we have been selective in adding to our research team. Only those whose other commitments do not put them at risk of being a “spreader” are currently able to join with us. If you think you meet that one qualification and are interested, let me know. Otherwise, the pandemic will not last forever, and so once it is again safe you are welcome to add your pair of “new eyes” to our team.

Go outside, tip your hat to a lizard, and stay safe.