On the mission of Conservation Biology

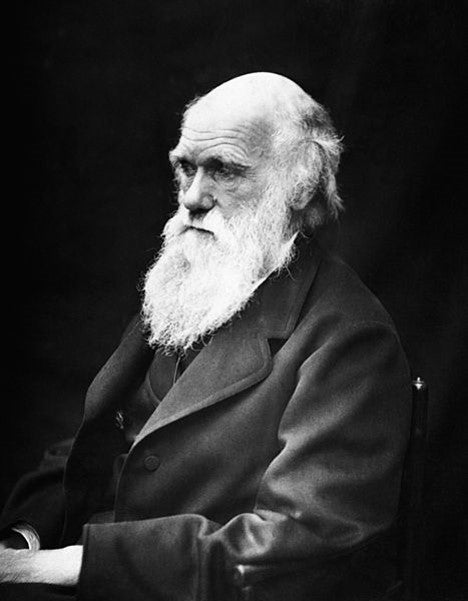

“It is interesting to contemplate an entangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and so dependent on each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by the laws acting around us. These laws, taken in the largest sense, being growth and reproduction; inheritance which is almost implied by reproduction; variability from the indirect and direct action of the external conditions of life, and from use and disuse; a ratio of increase so high as to lead to a struggle for life, and as a consequence of natural selection, entailing divergence of character and the extinction of less improved forms. Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most exalted object we are capable of conceiving, namely the production of higher animals directly follows. There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.”

– Charles Darwin, final paragraph of the first edition of the Origin of the Species

I wanted to share this with you, not because of the interminably long sentence-style of Victorian English, but rather as an insight into what I interpret he felt as a sense of awe of the beauty and complexity of nature. Darwinian scholars always point to this first edition as where you get the best glimpse of what Darwin wanted to say, and how he wanted to say it. In the following editions (six), Darwin changed phrases in response to criticisms he had received, always trying to mollify his detractors. We don’t always get the sense of how modern scientists feel about what they do and the animals and plants they work with; such emotions are sometimes frowned upon in the acceptable terse style of scientific papers.

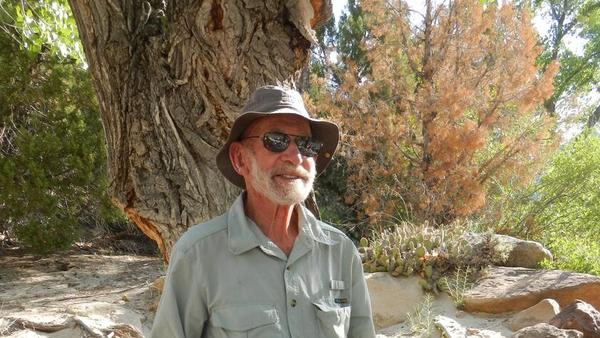

There are of course exceptions to the emphasis on objectivity approach to science. One of those is Natural History where we have the freedom to acknowledge the values nature gives us. Another, although in a different way, is Conservation Biology. Conservation biology is a mission-driven discipline, explicit in aiming to identify pathways — or barriers that need to be breached — to ensure that animals, and plants, and human animals, all continue to have a place to live and thrive on our planet. Michael Soulé conceptualized and catalyzed this new idea, this new scientific discipline called Conservation Biology in the 1970s. He was on the faculty at UC San Diego starting in 1967 but became dismayed at the rapid habitat loss occurring all around him. He resigned from UCSD and became the Director of a Buddhist Zen Center in Los Angeles. I once asked him about that career shift, moving away from what was certain to be a successful life in academia. He told me that while he was in the monastery it was the most productive period of his life. Long uninterrupted days of thinking deep thoughts about the relationships of people and nature. Conservation Biology was his answer and he then emerged, re-entered academia, and proceeded to change how science approaches nature. Unfortunately, Michael Soulé passed away earlier this summer.

I had the pleasure of meeting Michael a couple of decades ago right here in the Coachella Valley. I was then a member of a Scientific Advisory Committee, aimed at the design and implementation of the Coachella Valley Multiple Species Habitat Conservation Plan. Mark Fisher, Al Muth and I made up the core of this committee, and our goal was to have the best, most scientifically vetted conservation plan, ever. The scientific method requires peer review and so we needed a team of external scientists to evaluate our design. That team included Richard Tracy (University of Nevada Reno - tortoise guru – and father of the now Director of the Boyd Deep Canyon Desert Research Center, Chris Tracy), Howard Snell (University of New Mexico - Galapagos Island Iguana expert), Reed Noss (then-editor of the journal Conservation Biology), and Michael Soulé (Zen Master and then on the faculty of UC Santa Cruz). The common thread was they were all naturalists and mostly herpetologists (except Reed who was and is more of a big picture scientist). Michael did his PhD dissertation on lizards, focusing on side-blotched lizards inhabiting islands in the Gulf of California, Mexico.

Imagine having your photographs critiqued by Ansel Adams and Annie Leibovitz, your Thanksgiving dinner evaluated by Anthony Bourdain and Julia Child, or your tax returns checked by Katherine G. Johnson (“Hidden Figures” – developed the math that allowed John Glenn to safely orbit the earth and return home) or Rosalind Franklin (developed the analyses that allowed Watson and Crick to identify the double helix structure of DNA). That’s what we faced. However, as we quickly learned, this team was incredibly supportive of the work we had done — we passed!