Naturalist update from 7/18

I missed my Friday deadline once again – but no apology as I was out all day on the Deer Springs trail, just outside of Idyllwild, with community scientists conducting our annual lizard count. With Coachella Valley temperatures meeting or exceeding 110 degrees for the past weeks on end, it was refreshing to hike in temperatures that were in the mid-80s. Refreshing for both body and mind. After being inside for the past weeks toiling in front of my computer screen I did not even notice my soul slowly withering. Out on the trail, that euphoria of being in nature again was palpable. Get out, find a trail and that pandemic malaise evaporates. Even if temporary, it is a reminder of what used to be, and what will be again.

I recommend this trail. It is a moderate hike, not terribly steep, but unrelentingly uphill until you turn back, and then gravity is once again your friend. The trailhead is roughly at 5500’, and we climbed to about 7500’ in 3.5 miles, hiking under sugar, Coulter, and Jeffery pines, with a lower canopy of black, canyon live, and interior live oaks. One of the many treats was watching a mother black-headed grosbeak feed her lone fledgling.

But we were there to count lizards. Perhaps because this trail gets a lot of use from hikers, the lizards are habituated to we two-legged creatures passing by, and so they pay us little heed. That makes them easier to count.

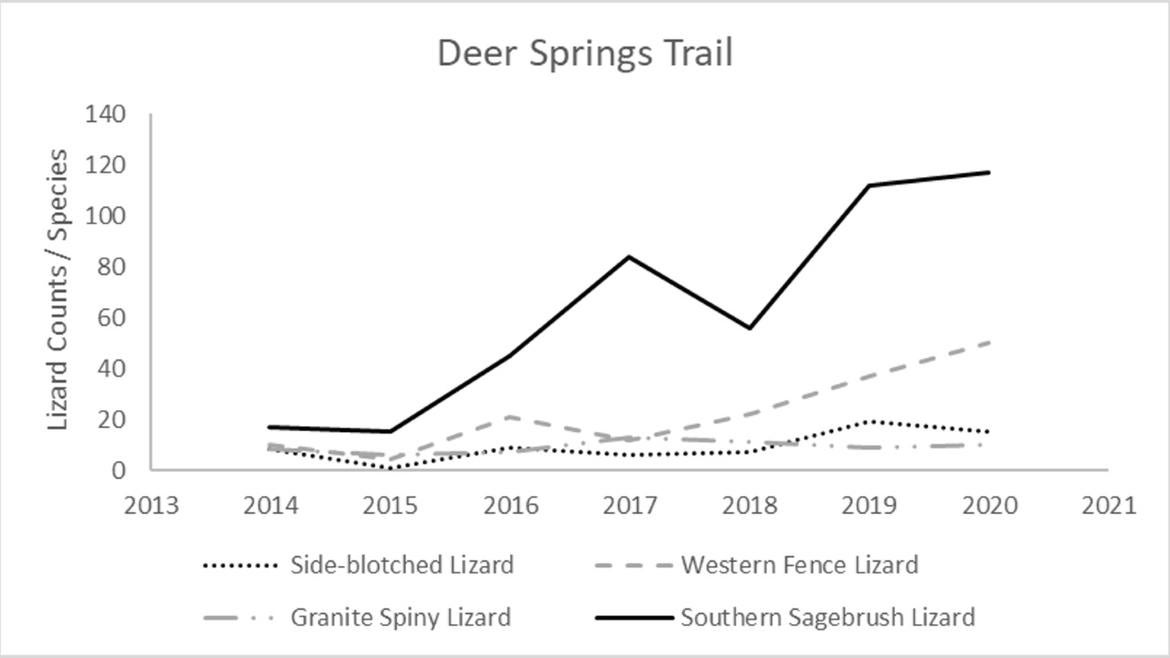

There are also a lot of lizards and several species: common side-blotched lizards, western fence lizards, granite spiny lizards, and southern sagebrush lizards. Our goal is to measure how the lizards are adjusting to a warmer and more arid world. This year we counted almost 200 (192) lizards, including many juveniles, a testament to the past few years that have been a bit wetter than average and good for lizard reproduction. Compare that to the counts during the hyper arid years of 2014 and 2015.

All four of these lizards seem to fill the same niche, eat insects, sit of rocks and logs, and make baby lizards. What makes this curious is that back, long, long ago, before smart phones and desktop computers, I used to spend hours in university libraries reading science journals to get the pulse of what questions scientists were asking. Back then (the 1970s) there was a common theme: describing how different species, living in the same place, avoided competition. Competition was THE driver of how natural communities were assembled, as no two species who filled the same niche could live in the same place. To live together they needed to use different subsets of the environment (rocks versus logs, small rocks versus big rocks, little bugs versus big bugs, ants versus beetles, nighttime versus daytime, morning versus afternoon, etc.). Otherwise, they simply could not live in the same habitat; paper after paper described how species partition their world and so then coexist. There was an apocryphal story of a graduate student returning from a season of field work and confessing to their professor that “as hard as they tried, they couldn’t find the niche separation between species A and species B." The professor then dismissively replied that the student “didn’t look hard enough."

So, how are these four lizard species partitioning their niches? Some are smaller (side-blotched lizards) and some get bigger (granite spiny lizards) and so likely eat different size insects, but there is a lot of overlap. One possibility is that in rain-limited environments like ours, there are other drivers rather than just competition. Extreme weather (droughts) and perhaps predation from birds and snakes, may keep these lizard populations from getting so dense that they are eating all the available food, and so never get to that level when they are competing with each other for food or space. Or maybe I am not looking hard enough.

Each of our lizard surveys turns into a “clinic” on how to identify each species. They do look a lot alike, but if we can’t distinguish one species from another, the data are garbage. Binoculars are a must, and there are subtle ways to identify each species:

Side-blotched lizards: exceptionally smooth scales on their back, a bit pointier snout, and for the coastal/mountain color type, cream-colored lines running from the head and down their back.

Southern sagebrush lizards: smooth back scales (but not so much as a side-blotched), a more rounded snout, and a broad dark stripe that starts on their cheek and splits at their shoulder with part continuing down their back and part wrapping around their shoulder.

Western fence lizards: scales noticeable coarser, a rounded snout, and a thin dark line extending from behind their eye and continuing down their back. Their eyelids are often tan colored and contrast with their gray body.

Granite spiny lizards: very coarse scales, a rounded snout, and for juveniles and females, yellowish bands (tiger stipes) extending the length of their body. Males can lack the bands, and can be uniformly almost black unless displaying bright breeding colors.

This week’s challenge is now to correctly identify the lizards in all the attached pictures, and send me your answers.

Stay safe, stay healthy and get outside.